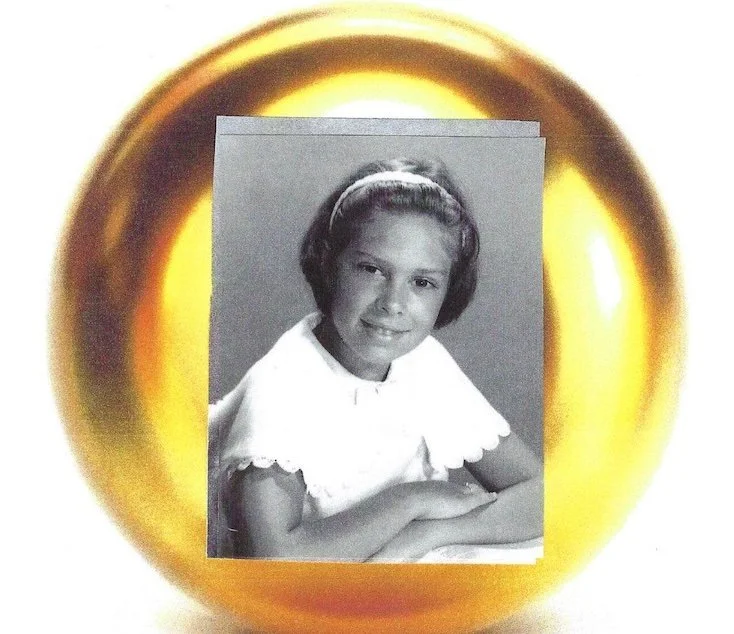

A little girl in our extended family is in third grade this year, stirring up deep feelings in me. How did she get so big? It’s wonderful how much she’s grown and learned. Even so, I find myself fervently wishing that I could protect her from the perils of this world.

You see, third grade was when I lost the golden ball.

In Iron John: A Book about Men, the poet Robert Bly writes of the innocence of a young boy as symbolized by a golden ball. The boy plays with this ball, enjoys it—and one day loses it. I’m summarizing wildly here, but you get the idea.

I first heard of Bly’s work when we were newly married and living in Atlanta. Jeff was reading a copy of Iron John and finding it deeply meaningful. “It explains so much!” he said, talking about Bly’s golden ball theory.

“Wait a sec,” I said. What made him think girls don’t go through something similar?

He looked a little sheepish, my feminist guy. Well, he admitted, it’s possible they do. But Bly was writing from a strictly male perspective. “Maybe it’s different for girls,” Jeff said. “Maybe there isn’t a single moment when it happens.”

So I told him my story.

It was a pretty spring day on a third grade playground, and kids from three classes were mingling and shouting and laughing. A group of boys was playing dodge ball. A half dozen girls were jumping rope. A second group of girls—mine—was galloping around, pretending to be a herd of wild horses. Other girls were hanging onto the railing for the broad concrete stairs that led inside, just standing there as a number of boys taunted them. They were playing what we called “boys chase girls.” It was a game we knew was frowned on by the adults, but we weren’t sure why.

The object of the game was for the girls to stray a few feet away from the staircase railing, which was Base, while the boys tried to “capture” them. Whenever a girl took a few taunting steps out from the stairs, the boys would lunge for her, hoping to grab her before she made it back to safety. How titillating it seemed, being desired and laid-in-wait-for. It stirred something in us we didn’t quite understand.

But I’d learned to stay away. One day I’d ventured too far off Base and been captured. I was pulled by several boys around to the back of the school, out of sight of the adults, to the delivery deck for the cafeteria where the fattest boy in the class was waiting. The boys pulled me along—I was laughing—and delivered me up to Fat Boy. He pushed me against the wall and shoved his whole large body up against mine, front to front, in a way that scared me. “You’re getting squished,” he said. He backed off and did it again, and again.

I didn’t play the game after that. It was much more fun galloping around with the wild horses.

One day when our herd had come to a grassy place in the hills where we could rest and graze, a boy named Alan approached us. “Hey Janice,” he said in a whiny voice, “You’re in the game.”

By then no one was calling me Janice; I was Jan. “I’m not in the game,” I said, and tossed my head.

“You are. I’ve seen you in it.”

“I’m NOT!” I turned to gallop away, but he grabbed my wrist and started dragging me toward the back of the school.

“Let go!” I struggled but couldn’t break free.

“You’re in the game,” he sneered. “I know you are.”

“Let go!” I yelled again, and when he wouldn’t I did what any wild stallion or filly would have done: I bit him. Hard, on his wrist. No way he was going to take me to that landing, out of sight of the adults.

He clutched at his wrist; I’d broken the skin. “You’re in trouble,” he said, and stormed off to find a teacher.

Why would I be in trouble? But I most certainly was. Our teacher, whom I loved, couldn’t fathom why I had acted so viciously—and I was at a loss to explain it.

That afternoon Alan and I had to write notes to each other’s parents, each telling our side of the story. Mine was immensely apologetic. I hadn’t meant to hurt him. I was surprised and sorry that I had. Alan’s began, “Your daughter bit me for no reason at all.”

My parents were flabbergasted. They looked at me a little differently, I thought. I was no longer their good, sweet girl. The shame this brought seemed bottomless.

“Your daughter bit me for no reason at all.” Hearing Jeff describe Bly’s theory of losing the golden ball took me back to the moment when my mother read Alan’s note. To the memory of being molested, the shock of having people question why I’d defended myself and not having the words to explain.

At some point we all lose the golden ball. It’s a rite of passage that can’t be avoided, I suppose. But my prayer for the third grader in our family is that her awakening will come in a way that’s kinder than it was for me.